Gen Z and Arabic: How tech reproduces the marginalization of language

Imagine living in a world where your phone, computer, and even the medical equipment that helped monitor your birth all operate in English. A world where the majority of your time on the internet is spent scrolling and reading through English content, typing and posting is in English, GPS clumsily pronounces Arabic street names in English accents, and the vast majority of virtual personal assistants (Siri, Alexa, etc.) speak in impeccable English.

There exists a prevalent perception among Egyptian Arabic-speakers of Generation (Gen) Z – roughly defined as those born between the late 1990s and the early 2010s - of Arabic as a second-rate or lesser language compared to English. I argue that this is, in part, due to the fact that the technologies we were exposed to all our lives are Eurocentric and better suited for use in English rather than Arabic.

While I won't feign any scientific rigor, I think a little experiment could help us better understand this perception. What follows is a questionnaire divided into two, completed by 30 of my friends and peers – all high-school-aged. It consists of three sections: the first explores the extent to which participants think in English, the second asks them to read either an article in English or its Arabic translation and evaluate it, and the third looks at their use of Arabic online.

Section 1

Question 1:

English: 28 (93.4%)

Arabic: 1 (3.3%)

“Arbic”[sic]: 1 (3.3%)

Consider the answers to the questions above. The fact that the vast majority responded that they think of their name in English first deserves some thought. The English language has become so natural to Gen Z that it’s what first comes to mind when we try to identify ourselves. Ironically, respondents think of their names in English first despite the inconsistent and sometimes awkward transliteration our names go through to be written in English. For example, there is no particular reason why I, “Selim,” am not “Sileem,” or why someone is “Mohammed” and not “Mohamed” or “Muhammad”; history just so happened to favor one transliteration over the other.

When I first discussed this with my peers, it was not uncommon to hear that envisioning the way their name looks in written Arabic felt like envisioning a different person (one who only ‘comes out’ during Arabic exams, some added).

Notice the positive skew on both graphs (barring the outliers that chose 1 and 2; if they were removed, the mean would be 7). You can see that a lot of people instinctively think in English even when reading and writing in Arabic, and that their Arabic in writing tends to be a word-for-word translation of English (although some participants do not believe this applies to them). Interestingly, Arab writers have been discussing this since at least the 1800s, with the most recent addition being Ahmed (or is it “Ahmad”?) Al-Ghamidi’s Al-‘Aranjiyyah (a portmanteau of ‘arabiyyah, Arabic, and ifranjiyyah, the Franks).

In his book, Al-Ghamidi goes to great lengths to argue that Western influence on modern Arabic goes much more beyond a few words or phrases and actually affects the structure of the language itself [1]. He also describes the history of what he calls ‘Asr al-Tarjamah (The Age of Translation), starting all the way back from Muhammad Ali’s reign over Egypt and the writers and scholars he would send to study and translate the works of Europe [2]. As these translations became textbooks at schools and colleges, and ‘aranjiyyah became an increasingly normal way to write, criticism wasn’t too far behind: one of the earliest examples is the late 19th-century writer Ibrahim Al-Yazigi’s Lughat Al-Jara’id (The Language of Newspapers) [3].

That last title should give you a hint as to how this links to technology. With the technological development of mass communication, the audiences of newspapers, newscasters, and mass media in general – the primary culprits of ‘aranjiyyah according to most in this genre – only grow larger. Although living in a world of technology can bring on a host of new problems, it also has the ability to exacerbate preexisting ones. The majority of online content in Arabic available for Gen Z consumption (which in itself is very limited) could easily be described as ‘aranjiyyah. This tweet perfectly illustrates some examples of ‘aranjiyyah with comparison to pre-modern Arabic literature.

Section 2

This section explains why the form is divided into two different versions. One version asks participants to look over the UN website’s front page and read a short article in English, and the other asks the remaining participants to read the same article in Arabic. The goal here is to compare any difference between the responses to both versions.

I’m as pleasantly surprised as I am sad that I don’t have much to write about for this section. Participants gave practically the same responses for both versions, even with similar distributions. Though this is speculation, I suspect that part of the reason for the relatively low score is related to ‘aranjiyyah and its normalization as a style of writing, to the extent that a person unaware of ‘aranjiyyah will assume that it is simply the normative way to write, despite its inherent awkwardness. A common theme I’ve seen when discussing this with friends is that those who do become aware of the concept can’t help but start seeing it in the things they read. In the words of one friend who read the Arabic article, “I gave the article a 3 in terms of the awkwardness of its writing, but rereading it with the whole ‘aranjiyyah thing now makes me want to give it at least a 7.”

Section 3

Question 1:

English: 29 (96.7%)

“Frnch” [sic] [4]: 1 (3.3%)

Question 2:

The past week: 15 (50%)

The past month: 4 (13.3%)

The past six months: 3 (10%)

The past year: 1 (3.3%)

Don’t remember: 7 (23.4%)

The goal with this section is to highlight how relatively small and inactive the Arabic digital world is compared to its English counterpart.

Note the answers to the first question: the irony of the only non-English language also being European shouldn’t be lost on anyone. Responses revealed that only half of participants had read anything in fusha Arabic in the past week, and almost a quarter did not remember when they last read something in fusha. Compare that with the daily use of our smartphones and the access they provide to an abundance of English content online.

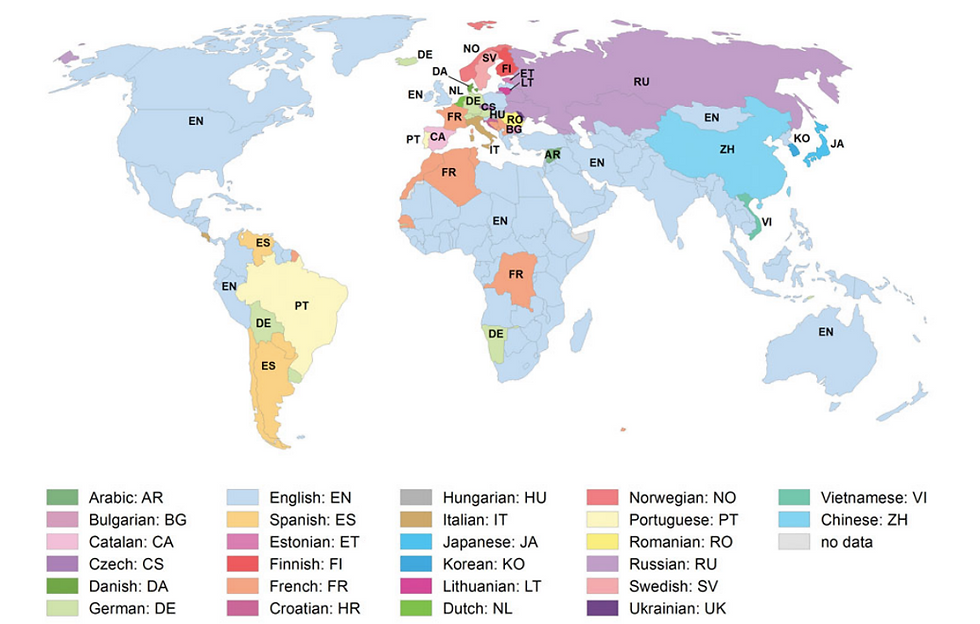

As indicated earlier, Arabic has a relatively small presence on the internet, making up only 5.2% of its users compared to English’s 25.9%. English is also the language of over 60% of the internet’s content, while Arabic doesn’t make it into the top 10[5]. Ubiquitous sites like Wikipedia also show a very stark contrast between English and Arabic, with its English language edition being by far its largest of its 288 official language editions. This divide, reflected in the map below, reveals colonial-era patterns of information production and representation [6].

Even when digital services and features are offered in Arabic, they tend to be less developed and even harmful when compared to their English counterparts, further exacerbating the problem. This is especially an issue for younger members of Gen Z: since any language comes with practice, losing out on using Arabic in the digital world due to the internet being mostly dominated by European languages means losing a major avenue of language practice and acquisition. This effectively creates a negative feedback loop: not using Arabic means becoming less proficient in it, and the less proficient you are at Arabic, the less likely you are to use it, and so on [7]. Ironically, when I asked the one person who set their phone to French why they did that, her response was that she was practicing her French in order to attend a French university.

One interesting area of development is how this all relates to ‘ammiyyah (colloquial) Arabic. Colloquial spoken Arabic lacks any consistent orthography, which can complicate the digitization of any language. However, social media applications like Instagram, Twitter, etc., are now able to understand and translate Franco (colloquial Arabic written with Latin script), a very welcome addition on the path to bringing Arabic into the digital world. Other initiatives that attempt to mitigate the digital linguistic divide include Majarra, a subscription service providing Arabic-language management and business content, and The Iraqi Translation Project, a project where volunteers translate open-source academic articles, educational videos, and documentaries into Arabic.

Conclusion

While conversations surrounding the future of the Arabic language have been a part of the MENA region for decades (and centuries), it is not unreasonable to say that in no generation has the topic been more pertinent than with Gen Z.

The first generation to live a completely digital life, Gen Z is at the center of a host of old and new issues when it comes to learning and practicing Arabic. In this article, I argued that this is partly due to the fact that the digital world is, by design, better suited for use in English, and other European languages rather than Arabic, which contributes to its marginalization among a generation that sees this world as an increasingly integral part of life.

As a brief final note, it should go without saying that one’s use of and reliance on technology in English isn’t generalizable to all Egyptians. For example, research shows that only 42.5% of the population are registered social media users, and that 57% live in rural areas[8], a significant predictor for ending up on the disadvantaged side of the digital divide[9], showing the effect of social cleavages on how one interacts with technology and its effect on their life.

NOTES:

[1]: أحمد الغامدي. العرنجية: بلسان عربي هجين. الطبعة الثانية.، دار التكوين، ٢٠٢٢م، ص ٣٦-٣٧

[2]: Ibid. ص ٢٦-٢٧

[3]: محمد خليل الزروق. أثر اللغات الإفرنجية في العربية العصرية، مناقشة كتاب (العرنجية)، ٢٠٢٢م

[4]: My thesis was only that we favor English over Arabic, not that we’re particularly good at either.

[5]: Ibrahimova, Mila. “The Languages in Cyberspace.” UNESCO, UNESCO, 29 Apr. 2021, https://en.unesco.org/courier/2021-2/languages-cyberspace.

[6]: Young, Holly. “The Digital Language Divide.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, http://labs.theguardian.com/digital-language-divide/ .

[7]: Veltman, Erica. “The Importance of Language Representation in Technology.” Explorations in Global Language Justice, Institute for Comparative Literature and Society, 5 Aug. 2020, https://languagejustice.wordpress.com/2020/08/04/the-importance-of-language-representation-in-technology/.

[8]: Kemp, Simon. “Digital 2022: Egypt - DataReportal – Global Digital Insights.” DataReportal, DataReportal – Global Digital Insights, 15 Feb. 2022, https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-egypt.

[9]: Badran, Mona Farid. “Young People and the Digital Divide in Egypt: An Empirical Study.” Eurasian Economic Review, vol. 4, no. 2, 2014, pp. 223–250., https://doi.org/10.1007/s40822-014-0008-z.

Kommentare