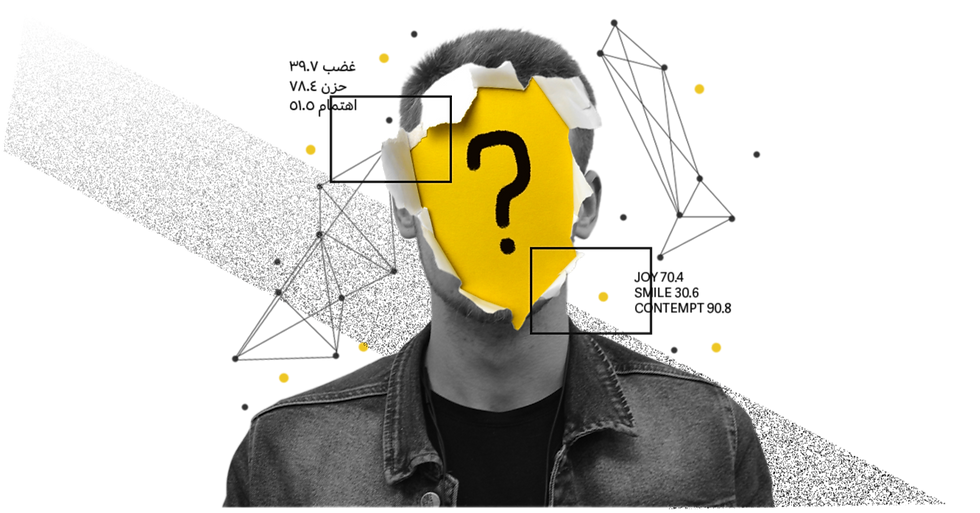

Are our emotions safe with AI in MENA? The risks of assuming universality in tech

In 1980, Australia was captivated by the heartbreaking story of Lindy Chamberlain, whose baby daughter, Azaria, disappeared during a family camping trip. Lindy claimed that a dingo, a wild Australian dog, had taken her child. Although deeply sympathetic at first, public opinion dramatically shifted when Lindy didn’t display the expected distress in interviews; she simply wasn't crying hard enough.

To them, this was a sign of her guilt. This shift in perception ultimately led to her being wrongfully convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. It was not until six years later that new evidence emerged proving Lindy’s innocence. Nonetheless, the case remains a compelling example of how the way we express emotions is embedded in our cultures and they influence the way we communicate, judge, and understand those around us. It also shows that though people may express emotions in varied ways, deviating from societal norms of emotional expression can lead to unfair judgment.

Now, let’s fast forward to today, Emotion Recognition AI (Emotion AI) has rapidly evolved into a multi-billion dollar global industry, and its influence is expanding into the MENA region. The technology is set to play a pivotal role in various critical sectors, including in healthcare, education, hiring, vehicle safety, and advertising. Its use holds the potential to bring positive change but also raises significant ethical and social concerns.

And, if Lindy Chamberlain's story taught us anything, it’s that we shouldn’t make hasty judgments based on someone's outward demeanor or draw life-altering conclusions from interpretations of facial expressions alone. So, when it comes to using Emotion AI in a region as diverse as the MENA, we need to exercise caution.

After all, can something as complex and subjective as emotion ever be truly quantified or accurately measured? Let's take a closer look.

Can AI quantify emotions?

Constructed emotion theory, a well-regarded theory among psychologists, describes emotions as psychological and physical subjective internal experiences unique to each individual, and asserts that there's no way to directly tap into someone else's feelings (qualia!). To add another layer of complexity, we ourselves often struggle to discern our own feelings—let alone those of others. For instance, think about the times you’ve sat with a therapist or friend, trying to untangle whether you’re feeling sad, angry, confused, or anxious. Or moments before giving a presentation, when your racing heart left you in a gray territory, somewhere between excitement and anxiety. This reinforces the idea that emotions are inherently unquantifiable. So, as you can imagine, interpreting emotions is not an easy task for humans, let alone for an AI.

The complexity of emotions presents a great challenge for Emotion AI, particularly because it relies only on what are known as “emotion proxies”, such as facial expressions, heart rate, and tone of voice to infer emotions. e While these proxies can provide some insight into our feelings, they cannot capture the full nuances of any single emotion accurately.

To interpret emotion proxies then, Emotion AI uses an emotion theory or “emotion model” as a guideline to label data from emotion proxies, helping the AI learn and make predictions. The most commonly used emotion model in Emotion AI is Paul Ekman’s Basic Emotion Theory (BET) from the 1970s, where a frown might be labeled as “sad,” or a smile as “happy,” based on the assumption that there are a number of basic emotions and microexpressions that are universal across all cultures. This and similar emotion models also assume that each emotion can be reliably detected from specific proxies only.

As a result, emotion AI models rely heavily on theories that oversimplify the nature of emotions. The BET model, for example, has been widely criticized by psychologists because it’s a theory based on studies where people were acting out what are essentially stereotypes of emotional facial expressions. In real-world contexts, expressions are far more varied; people might sob when they’re happy or keep a neutral face when they’re angry. Emotion expressions are also shaped by context and individual differences, and play an important role in how we convey meaning in social interactions.

This exposes a major flaw in models like BET: they reduce the multi-faceted and dynamic nature of emotions to simplistic categories, ignoring the nuanced and varied ways in which emotions can be expressed. This is also evidenced by recent research, including a meta-analysis by Dr. Barrett, that shows that there is no reliable way to detect emotions solely from facial expressions.

Can emotion recognition AI really be universal?

The assumption of universality of emotions is just another troubling assertion, one that is especially relevant to those of us in the MENA region. The concept of universality has been debunked by neuroscientists like Dr. Barrett and criticized for its risk and potential harm by experts like Dr. Kate Crawford. But to illustrate further why this assumption is false, I want to focus specifically on the MENA region.

Think of the words used to refer to universal basic emotions like “anger”, “sadness”, “fear”, and “interest” translating into Arabic as “ghaddab”, “huzn”, “khuf”, and “ihtemam”, respectively. While these Arabic words might be the closest translation, they describe different emotional experiences. For instance, “ihtemam” implies a deeper concern than the casual English “interest”. In fact, a study showed that Americans used the English terms to describe a wider range of facial expressions than Arabs did with the Arabic words. Yet, Emotion AI models are based on English-language sentiment analysis. This leads us to an important issue: adopting English emotion concepts as universal standards overlooks the fact that Arabic terms are rooted in distinct cultural contexts, literature, history, and carry different connotations and intensities.

Another study across nine Arabic-speaking countries found that, despite sharing the same language, people from different regions in MENA expressed emotions differently under stress, with religion and ethics influencing these expressions. This diversity underscores how emotion expression in the MENA region differs from Western norms. Thus, by using Emotion AI in the MENA region, based on Western emotional models, we risk inaccuracies in emotion interpretation.

Bias can creep in…

Additionally, there is the issue of variability within individuals. AI models work by identifying common patterns in large datasets, which they use as a "norm" to interpret new information. When data doesn’t fit these patterns, it can be misunderstood or ignored. This is particularly problematic for neurodiverse individuals, like those with autism or social anxiety, whose emotional expressions might not align with the norm, leading to misinterpretation by an AI. Similarly, emotion AI trained on biased data has been known to misinterpret black faces as showing "negative" emotions, like anger, more often compared to white faces.

This brings us to the broader issue of discrimination and bias in AI. When emotion AI relies on biased data, a simplistic Western-developed emotion model, while ignoring cultural and social contexts, it risks misreading people's true emotions and unfairly targeting or excluding individuals.

There are already many real-world examples of these issues. For instance, the MIT Technology Review podcast reported that emotion AI used in job interviews tends to favor candidates who sound confident, rather than focusing on what they actually say. This is especially dangerous when used to screen thousands of applicants with no human oversight. In another example, emotion AI in classrooms analyzes students’ body language and facial expressions and gives reports back to teachers and parents about students who may be distracted or cheating or even categorize them as “problem students” without fully understanding the context.

A feedback loop

These examples also lead us to another issue: as emotion AI becomes more widespread, the pressure to conform to its standards could start reshaping how people express their emotions.

In a study at the American University in Cairo (AUC), faculty were asked if they would consider using emotion AI in their classrooms. Several teachers expressed concerns that students might feel constantly monitored and unable to be themselves. This is a legitimate worry because, as the faculty noted, students have the right to zone out or lose concentration at times and it’s unrealistic to expect them to be fully engaged all the time. If implemented in classrooms to detect engagement or score students, this technology could lead students to deliberately control their emotional expressions to avoid being flagged as distracted or sleepy by an emotion AI system.

This concern, however, does not stop at the classroom door. In their paper, Dr. Luke Stark and Dr. Jessie Hoey discuss how AI could reshape emotional norms and could pressure people to alter emotional expressions to increase their chances of getting hired or avoid being flagged by surveillance. This means that by using the current emotion AI models in the MENA region, not only do we risk discriminating against vulnerable groups or ethnic minorities, we also risk altering the unique norms of emotional expression inherent to our culture and traditions.

Moving forward with Emotion AI

So, what can we do? One solution is to develop emotion AI with the aim of improving social conditions. This involves considering the context where emotion AI is used. For example, in hiring, there’s no proof that a particular way of expressing emotions predicts better job performance, making its use in this context unnecessary at best, and invalid and unfair at worst. In the EU AI Act, published in June of this year, there are moves to start banning emotion AI in schools, policing, and workplaces. While it is a step forward, some argue it doesn’t go far enough. In the MENA region, similar policies could be considered to ensure that emotion AI is used ethically and does not undermine cultural or individual diversity.

Some researchers in affective computing also suggest designing Emotion AI with reduced bias and improved validity. For the Middle East, this could mean MENA experts from fields like social science, psychology, and computer science coming together to create Emotion AI that considers the dynamic nature of emotions and the social and cultural contexts of the region. Until such an AI is developed, existing Emotion AI should be carefully monitored, regulated and tested.

Finally, the EAI ethics guidelines by Andrew McStay et. al., offer practical advice to address the problems of oversimplification and discrimination in Emotion AI. This advice includes understanding that the physical display of emotion is only one aspect of emotional experience and that past expressions don’t necessarily predict future feelings. Given how AI reflects the societal context where it’s developed, any biases present in society can be inadvertently inherited into it. Therefore, these guidelines also remind us to stay aware about how our assumptions about emotions can materially affect individuals and groups, whether in AI decisions or human judgments. They serve not just as a framework for AI, but as a call to reexamine how we, as a society, perceive and respond to emotional expressions in all forms of decision-making.

References

Abu-Hamda, B., Soliman, A., Babekr, A., & Bellaj, T. (2017). Emotional expression and culture: Implications from nine Arab countries. European Psychiatry, 41(S1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.2237

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Barrett, L. F., Adolphs, R., Marsella, S., Martinez, A. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2019). Emotional expressions reconsidered: Challenges to inferring emotion from human facial movements. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 20(1), 1–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100619832930

Hartmann, K. V., Rubeis, G., & Primc, N. (2024). Healthy and happy? an ethical investigation of emotion recognition and Regulation Technologies (ERR) within ambient assisted living (AAL). Science and Engineering Ethics, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-024-00470-8

Kappas, A. (2010). Smile when you read this, whether you like it or not: Conceptual challenges to affect detection. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 1(1), 38–41. https://doi.org/10.1109/t-affc.2010.6

Kayyal, M. H., & Russell, J. A. (2012). Language and emotion. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 32(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x12461004

Lambert, T. (2020, August 17). “why didn’t she cry?” how Lindy Chamberlain became the poster child for life-shattering gender bias. Women’s Agenda. https://womensagenda.com.au/latest/why-didnt-she-cry-how-lindy-chamberlain-became-the-poster-child-for-life-shattering-gender-bias/

Luusua, A. (2022). Katherine Crawford: Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of Artificial Intelligence. AI & SOCIETY, 38(3), 1257–1259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01488-x

McStay, A. and Pavliscak, P. (2019) Emotional Artificial Intelligence: Guidelines For Ethical Use.

Mohammad, S. M. (2022). Ethics sheet for automatic emotion recognition and sentiment analysis. Computational Linguistics, 48(2), 239–278. https://doi.org/10.1162/coli_a_00433

Mummelthei, V. (2024, June 10). AI and the Middle East, confronting the emotional biases of techno-orientalism: Decolonizing AI’s affective gaze through Middle Eastern lenses. Keine Disziplin – No Discipline. https://nodiscipline.hypotheses.org/3200

Sharawy, F. S. (2023).The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A Study on Faculty Perspectives in Universities in Egypt [Master's Thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/2095

Stark, L., & Hoey, J. (2021). The ethics of Emotion in Artificial Intelligence Systems. Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445939

Strong, J. (2021, July 1). Podcast: Want a job? the AI will see you now. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/07/07/1043089/podcast-want-a-job-the-ai-will-see-you-now-2/

Tobin, M., & Matsakis, L. (2021, January 25). China is home to a growing market for dubious “Emotion recognition.” Rest of World. https://restofworld.org/2021/chinas-emotion-recognition-tech/

Comments